Recently, I spent two weeks in the Comune di Ferrara, a city and municipality in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. Known as the “City of Bicycles”, Ferrara is widely considered to be the most cycle-friendly city in the country.

Each day, its streets host a steady flow of pedestrians and cyclists and the countless encounters that occur between them. Commuters moving with purpose, parents pushing babies in strollers, and older kids walking to and from school.

Ferrara’s streets are captivating, with a level of activity most U.S. cities rarely achieve outside of Open Streets events. I was lucky to stay at a hotel located on Via Giuseppe Garibaldi, which leads directly into the city centre and is constantly buzzing with people. Google Street View has a great snapshot of what Via Giuseppe Garibaldi looks like on a typical weekday, and if you continue southeast you can follow my daily route to the street’s end at the Piazza Municipal.

We know that streets don’t become like Via Giuseppe Garibaldi by accident. Likewise, places like Ferrara are not set in amber. Yet, I find that when American planners discuss European cities, their walkability is often largely attributed to age alone, with little mention of the work that has gone into keeping places like Ferrara safe and accessible to pedestrians and cyclists over the last 100 years.

Of course, density and compactness are both major tenets of walkability. People and places need to be located close enough so that destinations are easy to reach. The average person will only walk or bike so far before they decide that another mode of transportation is a better option. A community can have miles and miles of sidewalks and bike lanes, but if things are too spread out, they will go unused.

Older communities like Ferrara, that were developed before the mass adoption of the automobile, typically have a built-in level of density that is conducive to walking and biking. This generally gives them an edge over newer communities, that were designed to be traveled by car; however, density alone does not necessarily equal walkability. In fact, Ferrara is substantially less dense than some of the other Italian cities it outperforms on transportation measures.

So while Ferrara’s density and historically compact development pattern have set the city up for success, and it would be easy to attribute the community’s high rates of active transportation to these factors alone, it would also be an oversimplification. And worse, it would ignore the deliberate policy decisions that are required to maintain walkability in places like Ferrara over time.

Cars and People

Like the US, Italy experienced a period of motorization in the two decades that followed WWII (Italy’s auto industry followed a playbook similar to the one used by American car makers). During this time, rates of individual car ownership expanded dramatically across the county. By the 1970s, many Italian cities were experiencing significant vehicle traffic and high levels of congestion. The areas in and around their historic centers were impacted the worst by traffic, and the character of their communities was being jeopardized as a result.

I was surprised to learn that Italians actually have relatively high rates of car ownership compared to their European peers and Ferrara has a greater number of cars per capita than Italy’s national average.

Planners and City officials in Ferrara have long recognized that cars and people generally do not mix. They are under no illusion that all modes of transportation can or should be prioritized in all areas of the city.

Instead, they have a history of adopting policies that prioritize bicycle and pedestrian access in and around centers of activity and along routes to businesses and services that meet peoples’ daily needs. Outside of these areas, the roads have been designed to move cars safely and efficiently at higher speeds and a at safe distance from people.

By encouraging transportation modes where they make sense, Ferrara has remained connected, safe, and vibrant.

Zone Traffic Limitato

From a policy standpoint, the first and likely the most impactful transportation initiative has been the pedestrianization of Ferrara’s city centre.

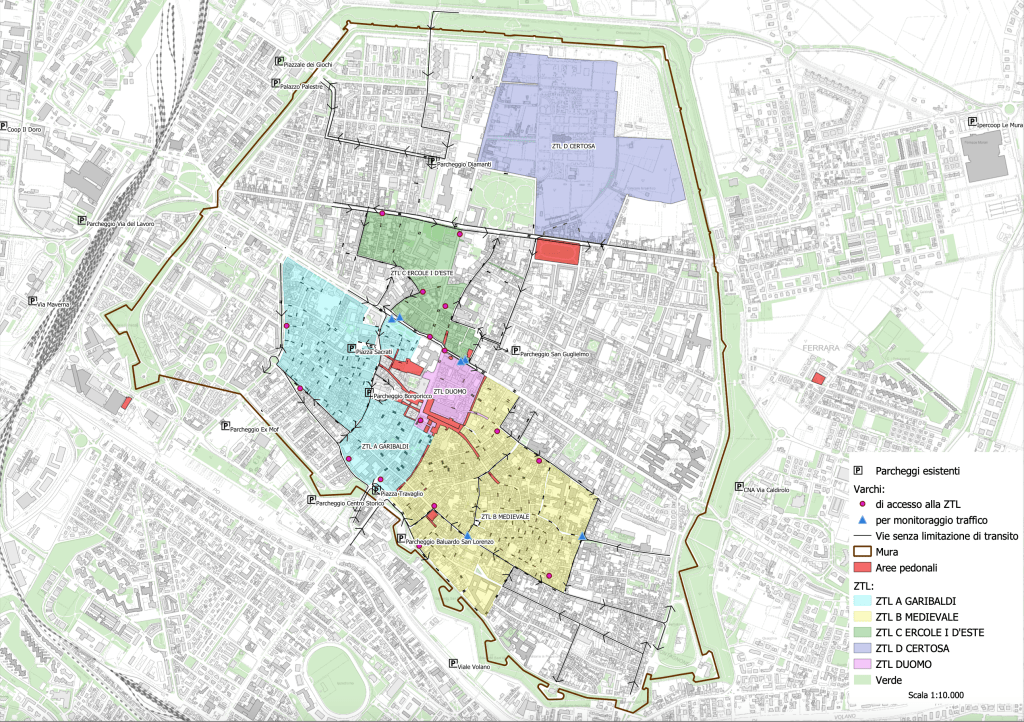

Ferrara was an early adopter of the la zona a traffic limitato or Traffic Limited Zone (ZTL), a traffic management policy designed to improve pedestrian access and combat congestion by restricting through-vehicle traffic in primary activity centers. The policy has been in place since the early 70s, and the city centre is now effectively car-free. Permits are granted only for residents of the area (capped at one vehicle per household) and a small number of exceptions are made for deliveries to residences, and building trades professionals.

The restrictions are tight and a very small number of vehicle trips occur within this area. Those that do occur are kept at a slow speed due to the narrow streets in the city centre and the surrounding areas.

Traffic Limited Zones are now common in many Italian cities (and they have caught on in other parts of Europe), but Ferrara was about twenty years ahead of the curve when it adopted its ZTL. In addition to being one of the first cities to adopt the policy, Ferrara stands out as having one of the largest areas dedicated to non-vehicular use, relative to the city’s size.

Currently, Ferrara’s Traffic Limited Zones include five nodes of activity, including a significant portion of the land within its original city limits, all reserved for non-vehicular use.

Outside of the ZTL

Outside of the ZTL, where cars, bikes, and people use the streets, the city has taken measures to ensure all can do so safely.

The entire Emilia-Romagna region is known for having decent cycling infrastructure, but over the last ten years, Ferrara has drastically expanded its bike network. Out of the fifty largest Italian cities, Ferrara now has the most kilometers of dedicated bicycle lanes per capita.

While the length and amount of Ferrara’s bicycle infrastructure is impressive, I was more impressed by how thoughtfully these improvements were made. In Ferrara, there are no bike lanes squished alongside busy arterial streets or sidewalks-to-nowhere on blocks that are too long. Ferrara is not performatively walkable and bikeable – it just is walkable and bikeable.

Ferrara’s street network includes many ancient narrow streets that extend from the city centre like spokes. Structures along them are built to the street and many are paved in stone. The vehicles that drive these streets are naturally slowed down by the traffic calming that is built-in, and pedestrians and cyclists are able to travel them safely without dedicated lanes.

Ferrara’s street network also includes several broad Renaissance-era streets that could have easily devolved into the street/road hybrids or “Stroads” that have made non-vehicular travel impossible or dangerous in many cities around the world (though Stroads are most common in North American, Europe is not immune). Coined by Charles Mahon of Strong Towns, “Stroads” are created when a right-of-ways attempts to be both a street (designed for people to move and connect WITHIN a place) and a road (designed to efficiently move people BETWEEN places). You can read more on Stroads here, but by attempting to achieve two competing goals, they fail at both. As a result, people are less safe and the street is no longer a place to spend time on or connect with the places around you. Instead, these wider streets have been updated with separated bike lanes and sidewalks. Where necessary, trees have been planted or bollards added to provide additional separation and protection.

Ferrara is currently in the process of developing a new Piano Urbanistico Generale (PUG) the Italian Comprehensive/General Plan. The public comment phase runs through the end of 2024, so specific planning goals and development policies are not available yet, but near the end of my trip I decided to stop by the Piazza Municipale where Ferrara’s planning staff were gracious enough to talk with me for a few minutes about what they are currently working on and their thoughts on Ferrara’s future.

The city is on top of becoming even more walkable by monitoring the mix of land uses (housing, workplaces, schools, healthcare facilities, retail, parks, and cultural amenities) that develop within an area to ensure residents can easily access their daily needs. They shared with me a map that demonstrates how easy it is to walk or bike to these key designations from various starting points.

All were located within incredibly easy distances for anyone residing in the main area of the city. I learned that a key future goal is to expand this level of multimodal access to residents of the nuclei of the countryside – small rural neighborhoods located outside of the city’s urban limits.

If this trajectory continues, it sounds like the city and the surrounding rural areas will soon become even more accessible.

Ferrarra’s activated streets are not simply the result of an impossible to replicate development history, or some cultural phenomenon that hates cars. They are the result of a long-standing recognition that not all modes of transportation can or should be prioritized in every area of the city, of good design and common sense policy decisions.

Failing to recognize the commitment and work required to maintain and continuously improve walkability in these places short-changes our European colleagues for their efforts, and ultimately, hurts our planning practice at home.

We have the opportunity to learn from communities like Ferrara. I hope we start to use it.